Israel's Prime Minister was a ruthless military commander responsible for one of the most shocking war crimes of the 20th century, argues Robert Fisk. President George Bush acclaims Ariel Sharon as 'a man of peace', yet the blood that was shed at Sabra and Chatila remains a stain on the conscience of the Zionist nation. As Sharon lies stricken in his hospital bed, his political career over, how will history judge him?

By Robert Fisk

The Independent

01/06/05

I shook hands with him once, a brisk, no-nonsense soldier's grip from Sharon as he finished a review of the vicious Phalangist militiamen who stood in the barracks square at Karantina in Beirut. Who would have thought, I asked myself then, that this same bunch of murderers - the men who butchered their way through the Palestinian Sabra and Chatila refugee camps only a few weeks earlier - had their origins in the Nazi Olympics of 1936. That's when old Pierre Gemayel - still alive and standing stiffly to attention for Sharon - watched the "order" of Nazi Germany and proposed to bring some of this "order" to Lebanon. That's what Gemayel told me himself. Did Sharon not understand this. Of course, he must have done.

Back on 18 September that same year, Loren Jenkins of The Washington Post and Karsten Tveit of Norwegian television and I had clambered over the piled corpses of Chatila - of raped and eviscerated women and their husbands and children and brothers - and Jenkins, knowing that the Isrealis had sat around the camps for two nights watching this filth, shrieked "Sharon!" in anger and rage. He was right. Sharon it was who sent the Phalange into the camps on the night of 16 September - to hunt for "terrorists", so he claimed at the time.

The subsequent Israeli Kahan commission of enquiry into this atrocity provided absolute proof that Israeli soldiers saw the massacre taking place. The evidence of a Lieutenant Avi Grabovsky was crucial. He was an Israeli deputy tank commander and reported what he saw to his higher command. "Don't interfere," the senior officer said. Ever afterwards, Israeli embassies around the world would claim that the commission held Sharon only indirectly responsible for the massacre. It was untrue. The last page of the official Israeli report held Sharon "personally responsible". It was years later that the Israeli-trained Phalangist commander, Elie Hobeika, now working for the Syrians, agreed to turn state's evidence against Sharon - now the Israeli Prime Minister - at a Brussels court. The day after the Israeli attorney general declared Sharon's defence a "state" matter, Hobeika was killed by a massive car bomb in east Beirut. Israel denied responsibility. US Defence Secretary Donald Rumsfeld traveled to Brussels and quietly threatened to withdraw Nato headquarters from Belgium if the country maintained its laws to punish war criminals from foreign nations. Within months, George W Bush had declared Sharon "a man of peace". It was all over.

In the end, Sharon got away with it, even when it was proved that he had, the night before the Phalangists attacked the civilians of the camp, publicly blamed the Palestinians for the murder of their leader, President-elect Bashir Gemayel. Sharon told these ruthless men that the Palestinians had killed their beloved "chief". Then he sent them in among the civilian sheep - and claimed later he could never have imagined what they would do in Chatila. Only years later was it proved that hundreds of Palestinians who survived the original massacre were interrogated by the Israelis and then handed back to the murderers to be slaughtered over the coming weeks.

So it is as a war criminal that Sharon will be known forever in the Arab world, through much of the Western world, in fact - save, of course, for the craven men in the White House and the State Department and the Blair Cabinet - as well as many leftist Israelis. Sabra and Chatila was a crime against humanity. Its dead counted more than half the fatalities of the World Trade Centre attacks of 2001. But the man who was responsible was a "man of peace". It was he who claimed that the preposterous Yasser Arafat was a Palestinian bin Laden. He it was who as Israeli foreign minister opposed Nato's war in Kosovo, inveighing against "Islamic terror" in Kosovo. "The moment that Israel expresses support...it's likely to be the next victim. Imagine that one day Arabs in Galilee demand that the region in which they live be recognised as an autonomous area, connected to the Palestinian Authority..." Ah yes, Sharon as an ally of another war criminal, Slobodan Milosevic. There must be no Albanian state in Kosovo.

Ever since he was elected in 2001 - and especially since his withdrawal of settlements from the rubbish tip of Gaza last year, a step which would, according to his spokesman, turn any plans for a Palestinian state in the West Bank into "formaldehyde" - his supporters have tried to turn Sharon into a pragmatist, another Charles de Gaulle. His new party was supposed to be proof of this. But in reality, Sharon had more in common with the putchist generals of Algeria.

He voted against the peace treaty with Egypt in 1979. He voted against a withdrawal from southern Lebanon in 1985. He opposed Israel's participation in the Madrid peace conference in 1991. He opposed the Knesset plenum vote on the Oslo agreement in 1993. He abstained on a vote for peace with Jordan in 1994. He voted against the Hebron agreement in 1997. He condemned the manner of Israel's retreat from Lebanon in 2000. By 2002, he had built 34 new Jewish colonies on Palestinian land.

And he was a man of peace.

There was a story told to me by one of the men investigating Sharon's responsibility for the Sabra and Chatila massacre, and the story is that the then Israeli defence minister, before he sent his Phalangist allies into the camps, announced that it was Palestinian "terrorists" who had murdered their newly assassinated leader, President-elect Gemayel. Sharon was to say later that he never dreamed the Phalange would massacre the Palestinians.

But how could he say that if he claimed earlier that the Palestinians killed the leader of the Phalange? In reality, no Palestinians were involved in Gemayel's death. It might seem odd in this new war to be dwelling about that earlier atrocity. I am fascinated by the language. Murderers, terrorists. That's what Sharon said then, and it's what he says now. Did he really make that statement in 1982? I begin to work the phone from Jerusalem, calling up Associated Press bureaus that might still have their files from 19 years ago. He would have made that speech - if indeed he used those words - some time on 15 September 1982.

One Sunday afternoon, my phone rings in Jerusalem. It's from an Israeli I met in Jaffa Street after the Sbarro bombing. An American Jewish woman had been screaming abuse at me - foreign journalists are being insulted by both sides with ever more violent language - and this man suddenly intervenes to protect me. He's smiling and cheerful and we exchange phone numbers. Now on the phone, he says he's taking the El-Al night flight to New York with his wife. Would I like to drop by for tea?

He turns out to have a luxurious apartment next to the King David Hotel and I notice, when I read his name on the outside security buzzer, that he's a rabbi. He's angry because a neighbour has just let down a friend's car tyres in the underground parking lot and he's saying how he felt like smashing the windows of the neighbour's car. His wife, bringing me tea and feeding me cookies, says that her husband - again, he should remain anonymous - gets angry very quickly. There's a kind of gentleness about them both - how easy it is to spot couples who are still in love - that is appealing. But when the rabbi starts to talk about the Palestinians, his voice begins to echo through the apartment. He says several times that Sharon is a good friend of his, a fine man, who's been to visit him in his New York office.

What we should do is go into those vermin pits and take out the terrorists and murderers. Vermin pits, yes I said, vermin, animals. I tell you what we should do. If one stone is lobbed from a refugee camp, we should bring the bulldozers and tear down the first 20 houses close to the road. If there's another stone, another 20 ones. They'd soon learn not to throw stones. Look, I tell you this. Stones are lethal. If you throw a stone at me, I'll shoot you. I have the right to shoot you.

Now the rabbi is a generous man. He's been in Israel to donate a vastly important and, I have no doubt, vastly expensive medical centre to the country. He is well-read. And I liked the fact that - unlike too many Israelis and Palestinians who put on a "we-only-want-peace" routine to hide more savage thoughts - he at least spoke his mind. But this is getting out of hand.

Why should I throw a stone at the rabbi? He shouts again. "If you throw a stone at me, I will shoot you." But if you throw a stone at me, I say, I won't shoot you. Because I have the right not to shoot you. He frowns. "Then I'd say you're out of your mind."

I am driving home when it suddenly hits me. The Old and New Testaments have just collided. The rabbi's dad taught him about an eye for an eye - or 20 homes for a stone - whereas Bill Fisk taught me about turning the other cheek. Judaism is bumping against Christianity. So is it any surprise that Judaism and Islam are crashing into each other? For despite all the talk of Christians and Jews being "people of the Book", Muslims are beginning to express ever harsher views of Jews. The sickening Hamas references to Jews as "the sons of pigs and monkeys" are echoed by Israelis who talk of Palestinians as cockroaches or "vermin", who tell you - as the rabbi told me - that Islam is a warrior religion, a religion that does not value human life. And I recall several times a Jewish settler who told me back in 1993 - in Gaza, just before the Oslo accords were signed - that "we do not recognise their Koran as a valid document."

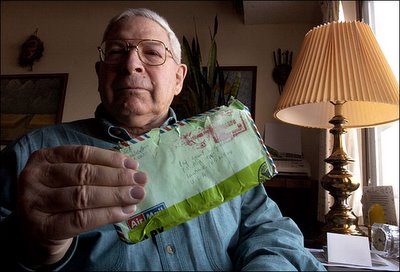

I call up Eva Stern in New York. Her talent for going through archives convinces me she can find out what Sharon said before the Sabra and Chatila massacre. I give her the date that is going through my head: 15 September 1982. She comes back on the line the same night. "Turn your fax on," Eva says. "You're going to want to read this." The paper starts to crinkle out of the machine. An AP report of 15 September 1982. "Defence Minister Ariel Sharon, in a statement, tied the killing [of the Phalangist leader Gemayel] to the PLO, saying: "It symbolises the terrorist murderousness of the PLO terrorist organisations and their supporters."

Then, a few hours later, Sharon sent the Phalange gunmen into the Palestinian camps. Reading that fax again and again, I feel a chill coming over me. There are Israelis today with as much rage towards the Palestinians as the Phalange 19 years ago. And these are the same words I am hearing today, from the same man, about the same people.

In September 2000, Ariel Sharon marched to the Muslim holy places - above the site of the Jewish Temple Mount - accompanied by about a thousand Israeli policemen. Within 24 hours, Israeli snipers opened fire with rifles on Palestinian protesters battling with police in the grounds of the seventh-century Dome of the Rock. At least four were killed and the head of the Israeli police, Yehuda Wilk, later confirmed that snipers had fired into the crowd when Palestinians "were felt to be endangering the lives of officers". Sixty-six Palestinians were wounded, most of them by rubber-coated steel bullets. The killings came almost exactly 10 years after armed Israeli police killed 19 Palestinian demonstrators and wounded another 140 in an incident at exactly the same spot, a slaughter that almost lost the United States its Arab support in the prelude to the 1991 Gulf War.

Sharon showed no remorse. "The state of Israel," he told CNN, "cannot afford that an Israeli citizen will not be able to visit part of his country, not to speak for the holiest for the Jewish people all around the world." He did not, however, explain why he should have chosen this moment - immediately after the collapse of the "peace process" - to undertake such a provocative act. Stone-throwing and shooting spread to the West Bank. Near Qalqiliya, a Palestinian policeman shot dead an Israeli soldier and wounded another - they were apparently part of a joint Israeli-Palestinian patrol originally set up under the terms of the Oslo agreement. "Everything was pre-planned," Sharon would claim five weeks later. "They took advantage of my visit to the Temple Mount. This was not the first time I've been there..."

Jerusalem is a city of illusions. Here Ariel Sharon promises his people "security" and brings them war. On the main road to Ma'ale Adumim, inside Israel's illegal "municipal boundaries", Israelis drive at over 100 mph. In the old city, Israeli troops and Palestinian civilians curse each other before the few astonished Christian tourists. Loving Jesus doesn't help to make sense of the Arab-Israeli conflict. Gideon Samet got it right in Ha'aretz. "Jerusalem looks like a Bosnia about to be born. Main thoroughfares inside the Green Line... have become mortally perilous... The capital's suburbs are exposed as Ramat Rachel was during the war of independence..." Samet is pushing it a bit. Life is more dangerous for Palestinians than for Israelis. Terrorism, terrorism, terrorism. "I suggest that we repeat to ourselves every day and throughout the day," Sharon tells us, "that there will be no negotiations with the Palestinians until there is a total cessation of terrorism, violence and incitement."

Gaza now is a miniature Beirut. Under Israeli siege, struck by F-16s and tank fire and gunboats, starved and often powerless - there are now six-hour electricity cuts every day in Gaza - it's as if Arafat and Sharon are replaying their bloody days in Lebanon. Sharon used to call Arafat a mass murderer back then. It's important not to become obsessed during wars. But Sharon's words were like an old, miserable film had seen before. Every morning in Jerusalem, I would pick up the Jerusalem Post. And there on the front page, as usual, will be another Sharon diatribe. PLO murderers. Palestinian Authority terror. Murderous terrorists.

Within hours of the 11 September 2001 attacks on the United States, Ariel Sharon turned Israel into America's ally in the "war on terror", immediately realigning Yasser Arafat as the Palestinian version of bin Laden and the Palestinian suicide bombers as blood brothers of the 19 Arabs - none of them Palestinian - who hijacked the four American airliners. In the new and vengeful spirit that President Bush encouraged among Americans, Israel's supporters in the United States now felt free to promote punishments for Israel's opponents that came close to the advocacy of war crimes. Nathan Lewin, a prominent Washington attorney and Jewish communal leader - and an often-mentioned candidate for a federal judgeship - called for the execution of family members of suicide bombers. "If executing some suicide bombers' families saves the lives of even an equal number of potential civilian victims, the exchange is, I believe, ethically permissible," he wrote in the journal Sh'ma.

When Sharon began his operation "Defensive Shield", the UN Security Council, with the active participation and support of the United States, demanded an immediate end to Israel's reoccupation of the West Bank. President George W Bush insisted that Sharon should follow the advice of "Israel's American friends" and - for Tony Blair was with Bush at the time - "Israel's British friends", and withdraw. "When I say withdraw, I mean it," Bush snapped three days later. But he meant nothing of the kind. Instead, he sent secretary of state Colin Powell off on an "urgent" mission of peace, a journey to Israel and the West Bank that would take an incredible eight days - just enough time, Bush presumably thought, to allow his "friend" Sharon to finish his latest bloody adventure in the West Bank. Supposedly unaware that Israel's chief of staff, Shoal Mofaz, had told Sharon that he needed at least eight weeks to "finish the job" of crushing the Palestinians, Powell wandered off around the Mediterranean, dawdling in Morocco, Spain, Egypt and Jordan before finally fetching up in Israel. If Washington firefighters took that long to reach a blaze, the American capital would long ago have turned to ashes. But of course, the purpose of Powell's idleness was to allow enough time for Jenin to be turned to ashes. Mission, I suppose, accomplished.

Sharon's ability to scorn the Americans was always humiliating for Washington. Before the massacres of 1982, Philip Habib was President Reagan's special representative, his envoy to Beirut increasingly horrified by the ferocity of Sharon's assault on the city. Not long before he died, I asked Habib why he didn't stop the bloodshed. "I could see it," he said. "I told the Israelis they were destroying the city, that they were firing non-stop. They just said they weren't. They said they werent doing that. I called Sharon on the phone. He said it wasnt true. That damned man said to me on the phone that what I saw happening wasn't happening. So I held the telephone out of the window so he could hear the explosions. Then he said to me: 'What kind of conversation is this where you hold a telephone out of a window?'"

Sharon's involvement in the 1982 Sabra and Chatila massacres continues to fester around the man who, according to Israel's 1993 Kahan commission report, bore "personal responsibility" for the Phalangist slaughter. So fearful were the Israeli authorities that their leaders would be charged with war crimes that they drew up a list of countries where they might have to stand trial - and which they should henceforth avoid - now that European nations were expanding their laws to include foreign nationals who had committed crimes abroad. Belgian judges were already considering a complaint by survivors of Sabra and Chatila - one of them a female rape victim - while a campaign had been mounted abroad against other Israeli figures associated with the atrocities. Eva Stern was one of those who tried to prevent Brigadier General Amos Yaron being appointed Israeli defence attaché in Washington because he had allowed the Lebanese Phalange militia to enter the camps on 16 September 1982, and knew - according to the Kahan commission report - that women and children were being murdered. He only ended the killings two days later. Canada declined to accept Yaron as defence attaché. Stern, who compiled a legal file on Yaron, later vainly campaigned with human rights groups to annul his appointment - by Prime Minister Ehud Barak - as director general of the Israeli defence ministry. The Belgian government changed their law - and dropped potential charges against Sharon - after a visit to Brussels by US defence secretary Donald Rumsfeld, the man who famously referred on 6 August 2002 to Israelis' control over "the so-called occupied territory" which was "the result of a war, which they won".

Rumsfeld had threatened that NATO headquarters might be withdrawn from Belgian soil if the Belgians didn't drop the charges against Sharon.

Yet all the while, we were supposed to believe that it was the corrupt, Parkinson's-haunted Yasser Arafat who was to blame for the new war. He was chastised by George Bush while the Palestinian people continued to be bestialised by the Israeli leadership. Rafael Eytan, the former Israeli chief of staff, had referred to Palestinians as "cockroaches in a glass jar". Menachem Begin called them "two-legged beasts". The Shas party leader who suggested that God should send the Palestinian "ants" to hell, also called them "serpents".

In August 2000, Barak called them crocodiles. Israeli chief of staff Moshe Yalon described the Palestinians as a "cancerous manifestation" and equated the military action in the occupied territories with "chemotherapy". In March 2001, the Israeli tourism minister, Rehavem Zeevi, called Arafat a "scorpion". Sharon repeatedly called Arafat a "murderer" and compared him to bin Laden.

He contributed to the image of Palestinian inhumanity in an interview in 1995, when he stated that Fatah sometimes punished Palestinians by "chopping off limbs of seven- and eight-year-old children in front of their parents as a form of punishment". However brutal Fatah may be, there is no record of any such atrocity being committed by them. But if enough people can be persuaded to believe this nonsense, then the use of Israeli death squads against such Palestinians becomes natural rather than illegal.

Sharon was forever, like his Prime Minister Menachem Begin, evoking the Second World War in spurious parallels with the Arab-Israeli conflict. When in the late winter of 1988 the US State Department opened talks with the PLO in Tunis after Arafat renounced "terrorism", Sharon stated in an interview with the Wall Street Journal that this was worse than the British and French appeasement before the Second World War when "the world, to prevent war, sacrificed one of the democracies". Arafat was "like Hitler who wanted so much to negotiate with the Allies in the second half of the second world war...and the Allies said 'No'. They said there are enemies with whom you don't talk. They pushed him to the bunker in Berlin where he found his death, and Arafat is the same kind of enemy, that with whom you don't talk. He's got too much blood on his hands."

Thus within his lifetime Sharon was able to bestialise Yasser Arafat as both Hitler and bin Laden. The thrust of Sharon's argument in those days was that the creation of a Palestinian state would mean a war in which "the terrorists will be acting from behind a cordon of UN forces and observers". By the time he was on his apparent death bed yesterday that Palestinian "state", far from being protected by the UN, was non-existent, its territory still being carved up in the West Bank by growing Jewish settlements, road blocks and a concrete wall.

Largely forgotten amid Sharon's hatred for "terrorism" was his outspoken criticism of Nato's war against Serbia in 1999, when he was Israeli foreign minister. Eleven years earlier he had sympathised with the political objective of Slobodan Milosevic: to prevent the establishment of an Albanian state in Kosovo. This, he said, would lead to "Greater Albania" and provide a haven for - readers must here hold their breath - "Islamic terror". In a Belgrade newspaper interview, Sharon said that "we stand together with you against the Islamic terror". Once Nato's bombing of Serbia was under way, however, Sharon's real reason for supporting the Serbs became apparent. "It's wrong for Israel to provide legitimacy to this forceful sort of intervention which the Nato countries are deploying... in an attempt to impose a solution on regional disputes," he said. "The moment Israel expresses support for the sort of model of action we're seeing in Kosovo, it's likely to be the next victim. Imagine that one day Arabs in Galilee demand that the region in which they live be recognised as an autonomous area, connected to the Palestinian Authority..."

NATO's bombing, Sharon said, was "brutal interventionism". The Israeli journalist Uri Avnery, who seized on this extraordinary piece of duplicity, said that "Islamic terror" in Kosovo could only exist in "Sharon's racist imagination". Avnery was far bolder in translating what lay behind Sharon's antipathy towards Nato action than Sharon himself. "If the Americans and the Europeans interfere today in the matter of Kosovo, what is to prevent them from doing the same tomorrow in the matter of Palestine?

"Sharon has made it crystal-clear to the world that there is a similarity and perhaps even identity between Milosevic's attitude towards Kosovo and the attitude of Netanyahu and Sharon towards the Palestinians." Besides, for a man whose own "brutal interventionism" in Lebanon in 1982 led to a Middle East bloodbath of unprecedented proportions, Sharon's remarks were, to say the least, hypocritical.

As Sharon sent an armoured column to reinvade Nablus, still ignoring Bush's demand to withdraw his troops from the West Bank, Colin Powell turned on Arafat, warning him that it was his "last chance" to show his leadership. There was no mention of the illegal Jewish settlements. There was to be no "last chance" threat for Sharon. The Americans even allowed him to refuse a UN fact-finding team in the occupied territories. Sharon was meeting with President George W Bush in Washington when a suicide bomber killed at least 15 Israeli civilians in a Tel Aviv nightclub; he broke off his visit and returned at once to Israel. Prominent American Jewish leaders, including Elie Wiesel and Alan Dershowitz, immediately called upon the White House not to put pressure on Sharon to join new Middle East peace talks. "This is a tough time," Wiesel announced. "This is not a time to pressure Israel. Any prime minister would do what Sharon is doing. He is doing his best. They should trust him." Wiesel need hardly have worried.

Only a month earlier, the Americans rolled out their first S-70A-55 troopcarrying Black Hawk helicopter to be sold to the Israelis. Israel had purchased 24 of the new machines, costing $211m - most of which would be paid for by the United States - even though it had 24 earlier-model Black Hawks. The log book of the first of the new helicopters was ceremonially handed over to the director general of the Israeli defence ministry, the notorious Amos Yaron, by none other than Alexander Haig - the man who gave Begin the green light to invade Lebanon in 1982.

Perhaps the only man who now had the time to work out the logic of this appalling conflict was the Palestinian leader sitting now in his surrounded, broken, ill-lit and unhealthy office block in Ramallah. The one characteristic Arafat shared with Sharon - apart from old age and decrepitude - was his refusal to plan ahead. What he said, what he did, what he proposed, was decided only at the moment he was forced to act. This was partly his old guerrilla training, a characteristic shared by Saddam. If you don't know what you are going to do tomorrow, you can be sure that your enemies don't know either. Sharon took the same view.

The most terrible incident - praised by Sharon at the time as a "great success" - was the attack by Israel on Salah Shehada, a Hamas leader, which slaughtered nine children along with eight adults. Their names gave a frightful reality to this child carnage: 18-month-old Ayman Matar, three-year-old Mohamed Matar, five-year-old Diana Matar, four-year-old Sobhi Hweiti, six-year-old Mohamed Hweiti, 10-year-old Ala Matar, 15-year-old Iman Shehada, 17-year-old Maryam Matar. And Dina Matar. She was two months old. An Israeli air force pilot dropped a one-ton bomb on their homes from an American-made F-16 aircraft on 22 July 2002.

What war did Sharon think he was fighting? And what was he fighting for? Sharon regarded the attack as a victory against "terror". Al-Wazzir, now an economic analyst in Gaza, believed that people who did not believe themselves to be targets were now finding themselves under attack. "There's a network of Israeli army and air force intelligence and Mossad and Shin Bet that works together, feeding each other information. They can cross the lines between Area C and Area B in the occupied territories. Usually they carry out operations when IDF morale is low. When they killed my father, the IDF was in very low spirits because of the first intifada. So they go for a 'spectacular' to show what great 'warriors' they are. Now the IDF morale is low again because of the second intifada."

Palestinian security officers in Gaza were intrigued by the logic behind the Israeli killings. "Our guys meet their guys and we know their officers and operatives," one of the Palestinian officials tells me. "I tell you this frankly - they are as corrupt and indisciplined as we are. And as ruthless. After they targeted Mohamed Dahlan's convoy when he was coming back from security talks, Dahlan talked to foreign minister Peres. "Look what you guys are doing to us," Dahlan told Peres. "Don't you realise it was me who took Sharon's son to meet Arafat?" Al-Wazzir understands some of the death squad logic. "It has some effect because we are a paternalistic society. We believe in the idea of a father figure. But when they assassinated my dad, the intifada didn't stop. It was affected, but all the political objectives failed. Rather than demoralising the Palestinians, it fuelled the intifada. They say there's now a hundred Palestinians on the murder list. No, I don't think the Palestinians will adopt the same type of killings against Israeli intelligence.

"An army is an institution, a system; murdering an officer just results in him the great war for civilisation 573 being replaced..." The murder of political or military opponents was a practice the Israelis honed in Lebanon where Lebanese guerrilla leaders were regularly blown up by hidden bombs or shot in the back by Shin Bet execution squads, often - as in the case of an Amal leader in the village of Bidias - after interrogation. And all in the name of "security".

Throughout the latest bloodletting, the one distinctive feature of the conflict - the illegal and continuing colonisation of occupied Arab land - was yet again a taboo subject, to be ignored, or mentioned in passing only when Jewish settlers were killed. That this was the world's last colonial conflict, in which the colonisers were supported by the United States, was undiscussable, a prohibited subject, something quite outside the brutality between Palestinians and Israelis which was, so we had to remember, now part of America's "war on terror". This is what Sharon had dishonestly claimed since 11 September 2001. The truth, however, became clear in a revealing interview Sharon gave to a French magazine in December of that year, in which he recalled a telephone conversation with Jacques Chirac. Sharon said he told the French president that: "I was at that time reading a terrible book about the Algerian war. It's a book whose title reads in Hebrew: The Savage War of Peace. I know that President Chirac fought as an officer during this conflict and that he had himself been decorated for his courage. So, in a very friendly way, I told him: 'Mr. President, you have to understand us, here, it's as if we are in Algeria. We have no place to go. And besides, we have no intention of leaving.'"

Sana Sersawi speaks carefully, loudly but slowly, as she recalls the chaotic, dangerous, desperately tragic events that overwhelmed her almost exactly 19 years ago, on 18 September 1982. As one of the survivors prepared to testify against the Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon - who was then Israel's defence minister - she stops to search her memory when she confronts the most terrible moments of her life. "The Lebanese Forces militia had taken us from our homes and marched us up to the entrance to the camp where a large hole had been dug in the earth. The men were told to get into it. Then the militiamen shot a Palestinian. The women and children had climbed over bodies to reach this spot, but we were truly shocked by seeing this man killed in front of us and there was a roar of shouting and screams from the women. That's when we heard the Israelis on loudspeakers shouting, "Give us the men, give us the men." We thought: "Thank God, they will save us." It was to prove a cruelly false hope.

Mrs Sersawi, three months pregnant, saw her 30-year-old husband Hassan, and her Egyptian brother-in-law Faraj el-Sayed Ahmed standing in the crowd of men. "We were all told to walk up the road towards the Kuwaiti embassy, the women and children in front, the men behind. We had been separated. There were Phalangist militiamen and Israeli soldiers walking alongside us. I could still see Hassan and Faraj. It was like a parade. There were several hundred of us. When we got to the Cité Sportive, the Israelis put us women in a big concrete room and the men were taken to another side of the stadium. There were a lot of men from the camp and I could no longer see my husband. The Israelis went round saying "Sit, sit." It was 11 o'clock. An hour later, we were told to leave. But we stood around outside amid the Israeli soldiers, waiting for our men."

Sana Sersawi waited in the bright, sweltering sun for Hassan and Faraj to emerge. "Some men came out, none of them younger than 40, and they told us to be patient, that hundreds of men were still inside. Then about four in the afternoon, an Israeli officer came out. He was wearing dark glasses and said in Arabic: "What are you all waiting for?" He said there was nobody left, that everyone had gone. There were Israeli trucks moving out with tarpaulin over them. We couldn't see inside. And there were Jeeps and tanks and a bulldozer making a lot of noise. We stayed there as it got dark and the Israelis appeared to be leaving and we were very nervous.

"But then when the Israelis had moved away, we went inside. And there was no one there. Nobody. I had been only three years married. I never saw my husband again."

The smashed Camille Chamoun Sports Stadium was a natural "holding centre" for prisoners. Only two miles from Beirut airport, it had been an ammunition dump for Yasser Arafat's PLO and repeatedly bombed by Israeli jets during the 1982 siege of Beirut so that its giant, smashed exterior looked like a nightmare denture. The Palestinians had earlier mined its cavernous interior, but its vast, underground storage space and athletics changing-rooms remained intact.

It was a familiar landmark to all of us who lived in Beirut. At mid-morning on 18 September 1982 - around the time Sana Sersawi says she was brought to the stadium - I saw hundreds of Palestinian and Lebanese prisoners, perhaps well over 1,000 in all, sitting in its gloomy, cavernous interior, squatting in the dust, watched over by Israeli soldiers and plainclothes Shin Beth agents and a group of men who I suspected, correctly, were Lebanese collaborators. The men sat in silence, obviously in fear.

From time to time, I noted, a few were taken away. They were put into Israeli army trucks or jeeps or Phalangist vehicles - for further "interrogation". Nor did I doubt this. A few hundred metres away, up to 600 massacre victims of the Sabra and Chatila Palestinian refugee camps rotted in the sun, the stench of decomposition drifting over the prisoners and their captors alike. It was suffocatingly hot. Loren Jenkins of The Washington Post, Paul Eedle of Reuters and I had only got into the cells because the Israelis assumed - given our Western appearance - that we must have been members of Shin Beth. Many of the prisoners had their heads bowed.

Arab prisoners usually adopted this pose of humiliation. But Israel's militiamen had been withdrawn from the camps, their slaughter over, and at least the Israeli army was now in charge. So what did these men have to fear?

Looking back - and listening to Sana Sersawi today - I shudder now at our innocence. My notes of the time contain some ominous clues. We found a Lebanese employee of Reuters, Abdullah Mattar, among the prisoners and obtained his release, Paul leading him away with his arm around the man's shoulders. "They take us away, one by one, for interrogation," one of the prisoners muttered to me. "They are Haddad militiamen. Usually they bring the people back after interrogation, but not always. Sometimes the people do not return." Then an Israeli officer ordered me to leave. Why couldn't the prisoners talk to me? I asked. "They can talk if they want," he replied. "But they have nothing to say."

All the Israelis knew what had happened inside the camps. The smell of the corpses was now overpowering. Outside, a Phalangist Jeep with the words "Military Police" painted on it - if so exotic an institution could be associated with this gang of murderers - drove by. A few television crews had turned up. One filmed the Lebanese Christian militiamen outside the Cité Sportive. He also filmed a woman pleading to an Israeli army colonel called "Yahya" for the release of her husband. The colonel has now been positively identified by The Independent. Today, he is a general in the Israeli army.

Along the main road opposite the stadium there was a line of Israeli Merkava tanks, their crews sitting on the turrets, smoking, watching the men being led from the stadium in ones or twos, some being set free, others being led away by Shin Beth men or by Lebanese men in drab khaki overalls. All these soldiers knew what had happened inside the camps. One, Lt Avi Grabovsky - he was later to testify to the Israeli Kahan commission - had even witnessed the murder of several civilians the previous day and had been told not to "interfere".

And in the days that followed, strange reports reached us. A girl had been dragged from a car in Damour by Phalangist militiamen and taken away, despite her appeals to a nearby Israeli soldier. Then the cleaning lady of a Lebanese woman who worked for a US television chain complained bitterly that Israelis had arrested her husband. He was never seen again.

There were other vague rumours of "disappeared" people. I wrote in my notes at the time that "even after Chatila, Israel's 'terrorist' enemies were being liquidated in West Beirut." But I had not directly associated this dark conviction with the Cité Sportive. I had not even reflected on the fearful precedents of a sports stadium in time of war. Hadn't there been a sports stadium in Santiago a few years before, packed with prisoners after Pinochet's coup d'état, a stadium from which many prisoners never returned?

Among the testimonies gathered by lawyers seeking to indict Ariel Sharon for war crimes is that of Wadha al-Sabeq. On Friday 17 September 1982, she said, while the massacre was still - unknown to her - under way inside Sabra and Chatila, she was in her home with her family in Bir Hassan, just opposite the camps. "Neighbours came and said the Israelis wanted to stamp our ID cards, so we went downstairs and we saw both Israelis and Lebanese forces on the road. The men were separated from the women." This separation - with its awful shadow of similar separations at Srebrenica during the Bosnian war - was a common feature of these mass arrests. "We were told to go to the Cité Sportive. The men stayed put." Among the men were Wadha's two sons, 19-year-old Mohamed and 16-year-old Ali and her brother Mohamed. "We went to the Cité Sportive, as the Israelis told us," she says. "I never saw my sons or brother again."

The survivors tell distressingly similar stories. Bahija Zrein says she was ordered by an Israeli patrol to go to the Cité Sportive and the men with her, including her 22-year-old brother, were taken away. Some militiamen - watched by the Israelis - loaded him into a car, blindfolded, she says.

"That's how he disappeared," she says in her official testimony, "and I have never seen him again since." It was only a few days afterwards that we journalists began to notice a discrepancy in the figures of dead. While up to 600 bodies had been found inside Sabra and Chatila, 1,800 civilians had been reported as "missing". We assumed - how easy assumptions are in war --that they had been killed in the three days between 16 September 1982 and the withdrawal of the Phalangist killers on 18 September, and that their corpses had been secretly buried outside the camp. Beneath the golf course, we suspected. The idea that many of these young people had been murdered outside the camps or after 18 September, that the killings were still going on while we walked through the camps, never occurred to us.

Why did we journalists at the time not think of this? The following year, the Israeli Kahan commission published its report, condemning Sharon but ending its own inquiry of the atrocity on 18 September, with just a one-line hint - unexplained - that several hundred people may have "disappeared around the same time". The commission interviewed no Palestinian survivors but it was allowed to become the narrative of history.

The idea that the Israelis went on handing over prisoners to their bloodthirsty militia allies never occurred to us. The Palestinians of Sabra and Chatila are now giving evidence that this is exactly what happened. One man, Abdel Nasser Alameh, believes his brother Ali was handed to the Phalange on the morning of 18 September. A Palestinian Christian woman called Milaneh Boutros has recorded how, in a truck-load of women and children, she was taken from the camps to the Christian town of Bikfaya, the home of the newly assassinated Christian President-elect Bashir Gemayel, where a grief-stricken Christian woman ordered the execution of a 13-year-old boy in the truck. He was shot. The truck must have passed at least four Israeli checkpoints on its way to Bikfaya. And heaven spare me, I had even met the woman who ordered the boy's execution.

Even before the slaughter inside the camps had ended, Shahira Abu Rudeina says she was taken to the Cité Sportive where, in one of the underground "holding centres", she saw a retarded man, watched by Israeli soldiers, burying bodies in a pit. Her evidence might be rejected were it not for the fact that she also expressed her gratitude for an Israeli soldier - inside the Chatila camp, against all the evidence given by the Israelis - who prevented the murder of her daughters by the Phalange.

Long after the war, the ruins of the Cité Sportive were torn down and a brand new marble stadium was built in its place, partly by the British. Pavarotti has sung there. But the testimony of what may lie beneath its foundations - and its frightful implications - will give Ariel Sharon further reason to fear an indictment.

I had been in the Sabra and Chatila camps when these crimes took place. I had returned to the camps, year after year, to try to discover what happened to the missing thousand men. Karsten Tveit of Norwegian television had been with me in 1982 and he had returned to Beirut many times with the same purpose. Lawyers weren't the only people investigating these crimes against humanity. In 2001, Tveit arrived in Lebanon with the original 1982 tapes of those women pleading for their menfolk at the gates of the Cité Sportive. He visited the poky little video shops in the present-day camp and showed and reshowed the tapes until local Palestinians identified them; then Tveit set off to find the women - 19 years older now - who were on the tape, who had asked for their sons and brothers and fathers and husbands outside the Cité Sportive. He traced them all. None had ever seen their loved ones again.

Extracted from The Great War For Civilisation: The Conquest of the Middle East, by Robert Fisk.